ORIGINAL in CityLab by Zak Accuardi

It’s not a death spiral—at least, not yet. Examples abound of how city leaders can turn the numbers around.

Any frank conversation about building better bus service in American cities must address one fact at the outset: Ridership is in free fall across the country.

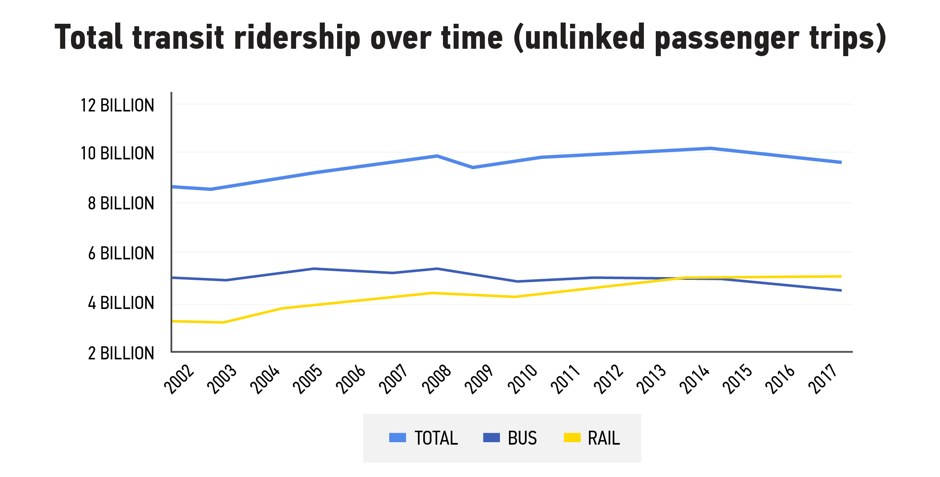

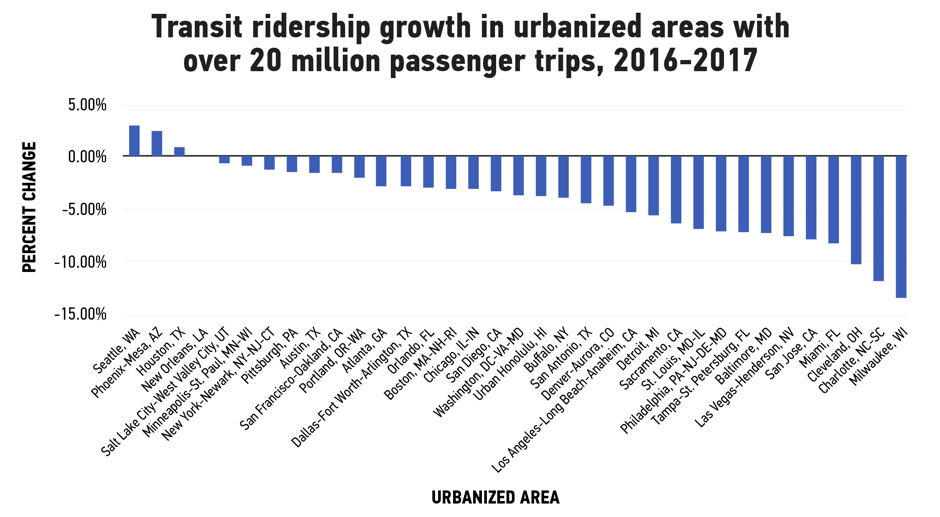

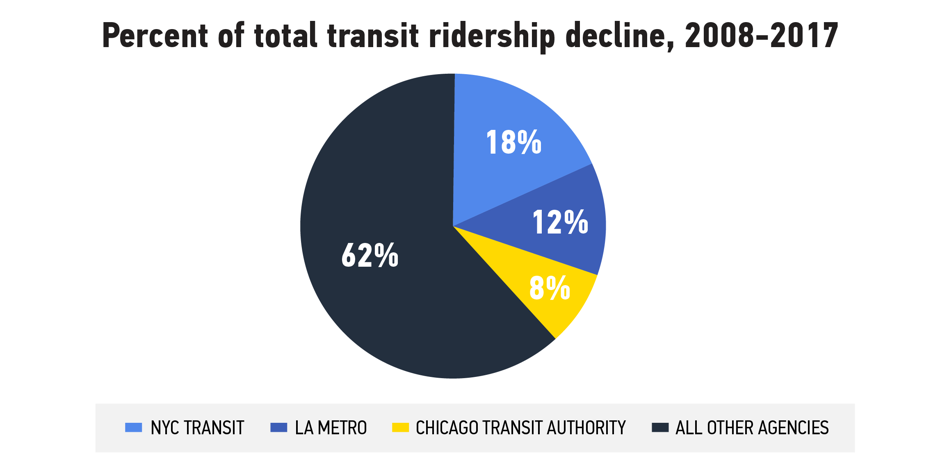

Numbers released last month from the Federal Transit Administration’s National Transit Database show a 2.5 percent decline in total transit ridership from 2016 to 2017, with bus ridership leading the way with a 5 percent drop. This nationwide decline in transit ridership has been in progress since 2014, despite growth in U.S. population and employment.

The result? More cars on the road, more traffic deaths, more lost time in longer commutes, and more pollutants in the atmosphere.

Ultimately, though, putting transit ridership back on an upward trend will require a sustained political commitment to improving local bus service. This is not a problem that our elected leaders can solve solely through technological innovation or big, shiny infrastructure projects. Instead, transit agencies and city leaders should work together to leverage transit’s most important competitive advantages—capacity and dedicated right-of-way—by giving priority to transit in the places where ridership and congestion justify it. Municipal support and coordination with transit agencies will define the destiny of urban transportation’s most underrated workhorse: the local bus.